Corruption in Singapore at Low Levels

Singapore is widely recognised as a country with zero-tolerance for corruption. The Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index 2016 ranked Singapore as the 7th least corrupt country in the world. Singapore has also maintained its first-place in the 2016 Political and Economic Risk Consultancy (PERC) annual survey on corruption.

2. In a recent essay on Singapore’s experience in combating corruption, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong commented that while Singapore has achieved some measure of success in fighting corruption, we are under no illusion that corruption has been permanently or completely eradicated. Corruption is driven by greed, and there will always be some individuals who are tempted to transgress. Corruption may be a fact of life, but will not be our way of life in Singapore as long as there is strong political will and leadership, and a culture which eschews corruption. We can then continue to keep corruption at bay and protect our hard-earned success and reputation.

Corruption complaints received and number of cases registered for investigation reach record low

3. In 2016, the CPIB received 808 complaints, an 8% decrease from the 877 complaints received in 2015 (Figure 1). In 2016, 118 cases (14.6%) from the 808 complaints received were registered for investigation[1] by the CPIB, compared with the 132 cases (15.1%) registered in 2015.

4. The complaints received by the CPIB were both corruption-related and non-corruption-related. For the past 3 years, about half the complaints received by the CPIB were non-corruption-related complaints, and these were referred to the relevant government authorities for their action. The quality and amount of relevant information of the corruption complaint received directly affects whether the case can be pursued. The majority of non-pursuable corruption complaints were due to insufficient, vague or unsubstantiated information provided.

What to include in a corruption complaint:

i. Where, when and how did the alleged corrupt act happen? ii. Who was involved and what were their roles? iii. How did you know about it? iv. Why do you think it is a corruption offence? v. What is the bribe transacted or favour shown? vi. Have you reported the matter to anyone else or/and any other authorities?

Figure 1: No of Complaints Received by CPIB vs No of Cases Registered for Investigation

Corruption complaints lodged in person remains the most effective mode

5. The majority (35%) of complaints received by the CPIB in 2016 were made through mail or fax, but these only accounted for 9% of the cases investigated. On the other hand, the 7% of complaints lodged in-person accounted for 26% of the cases investigated (Figure 2). Complaints lodged in-person are most effective because the CPIB can obtain more detailed information on suspected corrupt practices.

6. The CPIB takes a serious view of all complaints or information that may disclose any offence under the Prevention of Corruption Act. All complaints are deliberated upon by the Corruption Evaluation Committee (CEC), comprising members of the CPIB Directorate, regardless of the nature or amount of the gratification, or whether the complainant has identified himself or chosen to remain anonymous. The identity of complainants will also be kept confidential (Annex A details the process on how every corruption complaint received is managed).

Figure 2: Modes of Complaints Received vs Complaints Investigated in 2016

Private sector cases continued to make up majority of corruption cases in Singapore

7. Private sector cases continued to form the majority (85%) of all the cases registered for investigation by the CPIB, despite a 4% decrease from 2015. Of the private sector cases, 10% involved public sector employees rejecting bribes offered by private individuals. Public sector corruption cases remained at low, accounting for 15% of all cases registered for investigation in 2016 as compared to 11% in 2015 (Figure 3). Due to the small numbers, the increase of 4% from previous year is not significant.

Figure 3: Breakdown of the Cases Registered for Investigation by Private vs Public Sector

Custodial sentences were meted out to the majority of private sector employees

8. Over the past three years, the total number of individuals prosecuted for corruption offences remained low. In 2016, 104 individuals were prosecuted in Court for offences investigated by the CPIB. Of the 104 individuals, private sector employees made up 96%. Custodial sentences were meted out to the majority of these individuals for their corruption offences. Previously, the penalty meted out to private sector employees was a fine compared to public sector employees who were given jail terms for similar corruption offences. We have to recognise that corruption offences are serious breaches. In some instances, these offences may have far-reaching consequences negatively impacting the safety and security of our nation and the lives of ordinary folks. Therefore, stronger deterrence against corrupt practices applying to all individuals regardless of the nature of their employment is necessary.

9. Public sector employees continued to form the minority of individuals prosecuted for corruption. In 2016, four public employees were prosecuted in Court. Other public employees who were investigated were administered warnings or faced departmental action. The number of prosecuted public employees remained low at an average of less than 10% for the last three years (Figure 4).

10. Under the Prevention of Corruption Act, any person convicted of an offence is liable to a fine of up to $100,000, imprisonment for up to five years, or both. Where the offence involves a government contract or bribery of a Member of Parliament, imprisonment may be extended to seven years.

Figure 4: Public and Private Sector Employees Prosecuted in Court

11. Based on the cases of private sector employees prosecuted in Court for corruption-related offences in 2016, two main areas of concern were noted:

i. Maintenance work (e.g. inspection of electrical equipment, removal of copper cables, cleaning and water-proofing services); and

ii. Wholesale & Retail businesses (e.g. purchase and supply of fire safety, electrical and mechanical equipment).

Case study is appended in Annex B.

Clearance rate remains consistently high

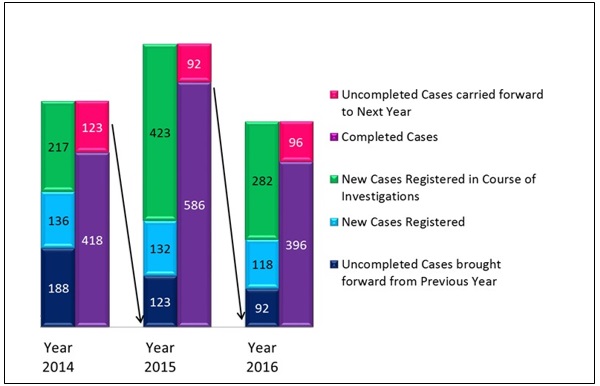

12. In 2016, the CPIB handled a total of 492 cases. This comprised 118 new cases registered from complaints lodged in the year, 282 new cases registered in the course of investigations and 92 uncompleted cases brought forward from 2015. (Figure 5).

13. The CPIB achieved a consistently high clearance rate[2] annually, clearing 80% of cases in 2016 (Figure 6).

Figure 5: No of Cases Handled in a Year

Figure 6: Yearly Clearance Rate

Highest conviction rate for CPIB cases

14. The strong commitment by the CPIB and the Attorney-General’s Chambers to bring corrupt offenders to task has contributed to a consistently high conviction rate for corruption-related offences. In 2016, the highest conviction rate at 100% was attained, a 3% increase from 2015 (Figure 7[3]).

Figure 7: Conviction Rate

Reaching out to the community

15. While the CPIB remains firm and resolute on the enforcement front, we have also expanded our outreach and public education efforts, enhancing public awareness on corruption matters through new engagement initiatives. Media publicity of individuals prosecuted for corruption offences also has a deterrent effect.

Educational exhibitions, virtual tour and mobile application

16. On 7 April 2016, the CPIB’s first roving exhibition “Declassified – Corruption Matters” and heritage trail mobile application “The Graftbusters Trail” were launched by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the National Library. The interactive exhibition, which attracted more than 15,000 visitors, featured never-before-seen information on the CPIB’s history, investigation officers and selected cases. More than 14,000 people also made a pledge to stamp out corruption and work together towards a corruption-free country. The exhibition then roved to various regional libraries in Jurong, Woodlands, Tampines and Bishan to spread the anti-corruption message to the Singapore heartlands. It has since made its appearance at the Institutes of Higher Learning, starting with the Republic Polytechnic. Visitors who missed the exhibition are treated to a virtual tour when they visit the CPIB website. Moreover, they can download the “The Graftbusters’ Trail” mobile application and get acquainted with the CPIB’s history and work.

CPIB Corruption Reporting & Heritage Centre @ 247 Whitley Road

17. The CPIB Corruption Reporting & Heritage Centre located at 247 Whitley Road commenced operations in January 2017. Members of public can now walk in to the new centre which is near Stevens MRT station (Downtown Line) to lodge corruption complaints. The Centre also houses a self-guided heritage gallery which showcases artefacts and key milestones from the Bureau’s rich history. Members of the public can continue to report suspected acts of corruption via the following channels:

i. Visit or write to us at the CPIB Headquarters @ 2 Lengkok Bahru, S159047 or Corruption Reporting & Heritage Centre @ 247 Whitley Road S297830;

ii. Call the Duty Officer at 1800-376-0000;

iii. Lodge an e-Complaint;

iv. Email us at report@cpib.gov.sg; or

v. Fax us at 6270 0320.

New private sector engagement initiatives

18. The majority of corruption cases in Singapore continues to come from the private sector. The CPIB has embarked on several new platforms and initiatives to engage the industry and business communities. A new guidebook, PACT: A Practical Anti-Corruption Guide for Businesses in Singapore has been developed to help local business owners reduce the risk of corruption in their companies. PACT sets out to guide business owners in developing and implementing an anti-corruption system in a clear and easy-to-understand manner, and includes useful information on corruption and corporate governance. PACT is available for download via the CPIB website.

19. ISO 37001 on Anti-Bribery Management Systems was launched on 15 October 2016. This is a new standard to help businesses and companies implement an anti-bribery compliance programme. It will enhance business competitiveness and protect employees and business associates from the risks of corruption. Supported by SPRING Singapore, the CPIB acted as the National Convenor to lead a national working group comprising representatives from the trade associations, industry bodies and academia to develop the standard. The CPIB, in partnership with SPRING Singapore, is planning its first private sector seminar in April 2017 to launch the Singapore Standard (SS ISO 37001).

Safeguarding Singapore’s future

20. Singapore’s international reputation for incorruptibility is hard-earned. The CPIB is resolute and committed in the battle against corruption to protect the integrity of our clean system of governance, as well as that of our well-regarded business and financial environment. Through active partnership with both our international partners and the local community, we can ensure that the scourge of corruption will never take root in Singapore, thereby safeguarding our nation’s future for generations to come.

Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau

Annex A

Annex B

Case-in-Point

Cleaning Contracts Stained With Corruption

Engaging in corrupt contracts is illegal and has landed the perpetrators in serious trouble.

The players

Mohamed Esa Bin Ismail (“Mohamed Esa”), a Director and Deputy Group Chief Executive Officer of Campaign Complete Solutions Pte Ltd (“Campaign”), was responsible for the operations of Campaign which provides cleaning services to commercial buildings and shopping malls. Andy Laurens @ Abdul Rahim Bin Abdullah (“Andy Laurens”), a Senior Manager of Singconex Management Pte Ltd (“Singconex”), was responsible for the operations of Singconex, including sub-contracting out cleaning services.

The corrupt act

Sometime in late 2008, Mohamed Esa had approached Andy Laurens and started to give him cash gratifications so as to advance the business interests of Campaign with Singconex. Both had known each other since 1986 when they were colleagues at Campaign. Singconex is a client of Campaign and had sub-contracted out cleaning services for tenants located at Suntec City Mall to Campaign. Andy Laurens understood that the purpose of the cash gratifications was to ensure that Singconex continued to support Campaign as a preferred vendor, and award the cleaning contracts to them. Between November 2008 and March 2014, Mohamed Esa had directly given or authorised a total of 57 cash payments, ranging from $1,500 and $2,077 per month, as a form of corrupt gratification to Andy Laurens. The total amount of cash gratification involved amounted to $88,024.

The punishment

In 2016, Mohamed Esa and Andy Laurens pleaded guilty and were sentenced to 18 weeks’ and 3 months’ imprisonment respectively for corruption.

[1] Cases registered for investigation refer to the pursuable cases opened from the complaints lodged.

[2] Clearance rate refers to the number of cases where investigations have been completed, out of the total number of cases investigated by the CPIB in a year.

[3] The conviction rate in Figure 7 excludes withdrawals.